[Long version] Does finishing skill matter in soccer?

Because it hasn't been discussed enough already

[Note: I make liberal use of footnotes for deeper discussion. Read them if you’re interested, or skip them if you’re not; they aren’t necessary for understanding the main text]

TL;DR

Using Bayesian inference on over 550,000 shots in men’s professional soccer from 2017-2018 until 2023, and defining finishing skill as over- or under-performance of xG, I estimate that the standard deviation in player finishing skill is a roughly 11% difference in scoring rate on an average set of shots.

With the same model, I’m able to estimate each individual player’s finishing skill (including confidence intervals) after optimally controlling for noise resulting from low sample sizes. For example, after accounting for sample size noise, the model’s best estimate is that on average, Harry Kane will score ~44.5% more goals than Patrick Bamford given the same set of shots.

Background

Let me confess: when it comes to soccer, I don’t know much. Tactical discussions fly over my head. I couldn’t really tell you why player A is better or worse than player B.

So, why should you read anything I write about the sport? Well, I’m a statistics and ML practitioner. And with the skillset that entails, there’s one area where I do feel I have something to offer: shooting.

Aside from set pieces, shooting is perhaps the single most discrete and regular part of soccer. And these days, we have detailed and consistent data for every shot, which in turn fuels powerful predictive models like xG. This makes shooting relatively amenable to data analysis, which I do know something about.

So today, I’d like to dive into…finishing skill!

Here we go again

I know, I know. If you’ve spent any amount of time reading about soccer analytics, you’ve heard it all before.

But if you haven’t, Mike Goodman gives an excellent overview of the perennial Finishing Skill Debate in his 2014 article, “Thinking About Finishing Skill”:

In general the debate boils down to three specific questions: What is finishing skill? Does it exist at all? Even if it does exist, does it matter?

My post today will focus mainly on that last question — “does it matter?” — but first, allow me to address the other two.

First, what is finishing skill? For technical analysis, probably the most reasonable way to define it is as a player’s ability to score a chance, after controlling for every other variable that is not a part of finishing. Still, this leaves the task of defining exactly which of a shooter’s actions are and are not a part of “finishing”.

For the purposes of this article, I’ll define finishing skill as a player’s ability to score more goals than predicted by xG. Implicitly, this means I’m defining “finishing” to include all shooting actions that aren’t controlled for in the particular xG model being used. Given the controls in the specific xG model I draw on1, this definition of finishing will include skills like shot placement and velocity, while excluding skills like the ability to dribble into better shooting positions. While not perfect, defining finishing skill in this way — i.e. in relation to xG — is a reasonable proxy, and gives us a mathematically clean concept.

Second, does finishing skill exist? To me this is a less serious question: as long as we define “finishing” to include at least some very basic shooting qualities like placement or power, then obviously some players will be better at it than others, i.e. it’s a skill.

Finally, the question I’ll focus on for the remainder of this post: does finishing skill matter?

To my mind, when we ask this question, we’re really asking: “Does finishing skill vary a lot between players?” If yes, then different players would convert xG to goals at very different rates, meaning finishing would play an important role in determining how good a player is at scoring goals, relative to other players.

So, the main question I’ll seek to answer in this post is: after controlling for statistical noise, how much does finishing skill vary across professional players?

In addition to quantifying variance, the model I develop will be able to do fun things like:

So, let’s get on with it!

Methodology

This section will involve some fairly technical discussion of statistics. If you’re fine accepting my methodology, feel free to skip ahead to the Results section.

How to quantify variance?

Without going too deep in the weeds, know that estimating variance in a “hidden” attribute like finishing skill is a deceptively hard problem.

The most obvious approaches — for example calculating the standard deviation in G/xG across players — will overstate the variance because they treat all variation as meaningful, when in reality much (maybe even most) of the observed variation is just noise resulting from low sample sizes.

Meanwhile, more subtle approaches that correct for noise — for example, regularized fixed effects regression — are likely to understate the variance, since they conservatively “squish” player estimates toward the average (a phenomenon known as shrinkage) when sample sizes are low; and sample sizes are always low when we’re talking about the shots taken by a single player.

The modeling approach outlined in the next section avoids both of these pitfalls by explicitly encoding “standard deviation in true (hidden) finishing skills” as a variable, then using computational statistics to estimate it.

Model

I use a fixed effects logistic regression, specified as a Bayesian hierarchical model, to estimate finishing skills for each individual player as well as the level of finishing skill variance across the entire player population.

The logistic regression models the probability each shot is scored, using the shot’s xG together with shooter- and goalkeeper-specific “skill” coefficients that move a shot’s goal probability up or down from xG. I interpret the shooter-specific coefficients as a measure of each player’s finishing skill.

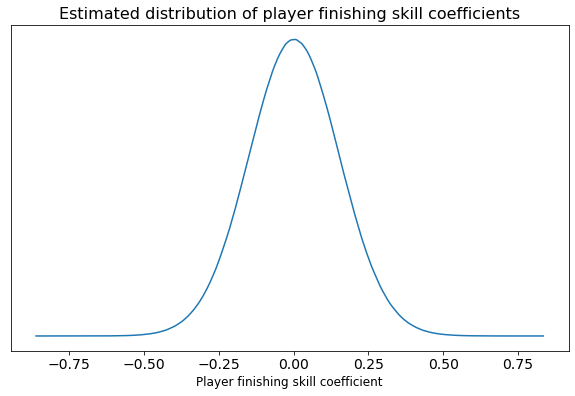

The interesting part of the methodology is Bayesian hierarchical modeling. In this approach, we assume that the model coefficients (in this case player finishing skills) come from some population distribution, like a normal distribution. For example:

But importantly, we tell the model “we don’t know exactly what this distribution looks like; could you figure it out for us?” Then, the model uses the data at hand, together with some Bayesian machinery2, to do exactly that.

Why does this work? Since we explicitly encode the mechanics of both skill and noise in the model, the Bayesian machinery is able to look at the level of variation observed in the data, “subtract out” the variation expected from noise due to low sample sizes, and attribute any remaining variation to actual variance in skill.

And as an added benefit, since the model has a sense of the overall skill variance, it’s able to adjust its individual player skill estimates accordingly: how far each player’s estimated skill deviates from the average depends not only on their own performance and sample size, but also on the level of overall variance the model is picking up on.

This methodology — namely, fitting a fixed effects regression with Bayesian priors to estimate player finishing skills — builds on the technical approach taken by Marek Kwiatkowski in his excellent 2017 article “Quantifying Finishing Skill”. My model is very similar to Marek’s, with a few key differences:

Rather than building my own xG model, I rely on already-existing xG estimates

In addition to shooter-specific finishing skill coefficients, I also throw in goalkeeper-specific coefficients (sort of a measure of shot-stopping skill, though not a very good one3). This should yield more precise finishing skill estimates by controlling for variance that would otherwise be unexplained4, i.e. how does this specific GK change the difficulty of the shot?

Most importantly, rather than use a fixed variance for the skill distribution (Marek uses a fixed standard deviation of 0.01), I instead ask the model to explicitly estimate the variance in player finishing skills, as detailed above

Data

To fit the model, I was able to acquire men’s shot data including xG.

The dataset includes 600,000+ shots across 11 domestic leagues, 3 European continental tournaments, and the World Cup and Euros. For most of these leagues, the data covers the 5-6 most recent seasons (as of summer 2023)5. More than 10,000 shooters and 1,000 goalkeepers are represented.

Throughout the analysis, I always filter out penalty kicks and free kicks, since these seem like a very different skill than open-play shooting. And I’ll always note which other filters are applied and roughly how many shots, shooters, and GKs remain.

Results

To start, I fit the model including players from all positions and leagues. To reduce the computational load of fitting the model, I restricted to shooters with at least 10 open-play shots. In the end, this left me with ~550,000 shots taken by more than 7,000 shooters against more than 1,000 goalkeepers.

Variance

All players

Again, my primary goal here is to quantify finishing skill variance. Drum roll…

The model estimates a mean standard deviation in player finishing skill of 0.153, with a 99% chance that the standard deviation is between 0.129 and 0.176.

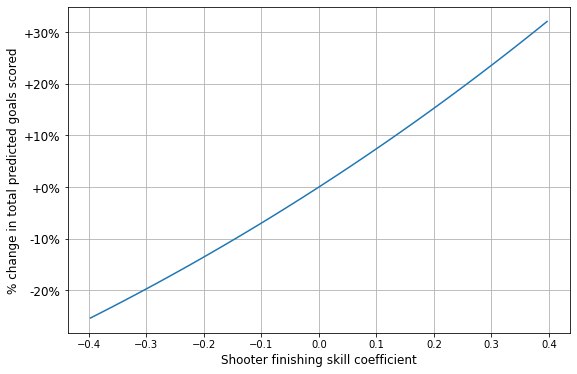

But what do these numbers like 0.153 actually mean? They refer to coefficients in a logistic regression, but what we’re interested in is probably more along the lines of “impact on goals scored”. And converting from logistic regression coefficients to goal impact is tricky, since a single coefficient value has a different impact depending on the baseline xG: for example, a 0.2 coefficient will increase the probability of scoring by 17% for a 0.2 xG shot, but by only 10% for a 0.5 xG shot.

To work around these peculiarities and convert our mysterious “coefficients” into more intelligible “goal modifiers”, I used the regression model to predict the total number of goals scored across all 550,000 shots given different coefficient values, like -0.1, 0.1, etc. Then, instead of reporting coefficient values themselves, I can report the % change in total predicted goals resulting from those particular coefficient values.

Below is the result of this exercise, a mapping from finishing skill coefficients to % change in predicted goals scored using all shots in the data:

Now, given the estimated variance in player finishing skill coefficients together with the effect of those coefficients on goal-scoring probability, we can say that for some average set of shots, the standard deviation in goals scored due to finishing skill is likely around 11%. Some implications of this:

On average, a “medium good” finisher (75th percentile) is ~15.9% more likely to score than a “medium bad” finisher (25th percentile) given the same shot

Put differently, 1 xG for a “medium good” finisher is worth on average ~1.159 xG for a “medium bad” finisher

A 90th percentile finisher is ~32.5% more likely to score than a 10th percentile finisher given the same shot

If you select any two players at random, on average their finishing skill disparity will be such that they have an ~13.7% difference in the likelihood of scoring the same shot

Only prolific Big 5 forwards

The results above were estimated across all leagues in my dataset, and for players of all positions. But maybe finishing skill variance is much lower among forwards, especially those in top leagues?

To check this, I reran the analysis, but restricting to only forwards — players listed as either “FW” (often strikers) or “FW,MF” (often wingers) on FBRef — with at least 100 open-play shots in Big 5 leagues, leaving ~110,000 shots, 506 shooters, and 441 GKs.

For this group of top attackers, the model estimates finishing skill standard deviation is ~0.147, very similar to the 0.153 estimated for all players. (Though it’s worth noting that due to much lower sample size, there’s more uncertainty in the estimated standard deviation: the 99% confidence interval ranges from 0.103 to 0.189)

So, the evidence suggests that finishing skill varies by a roughly similar amount among top forwards as it does across the entire player pool.

Individual player skill estimates

Now for the fun part! (For the remainder of this section, I go back to the model fit on ~550,000 open-play shots across all leagues and positions)

Finishing skill

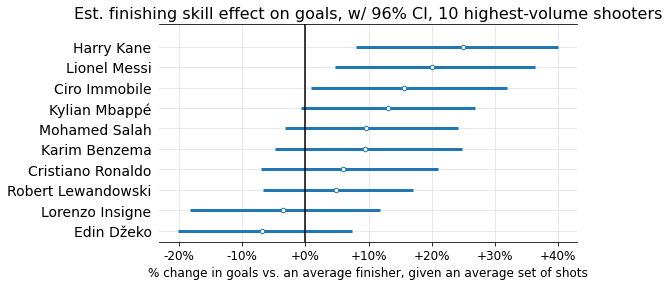

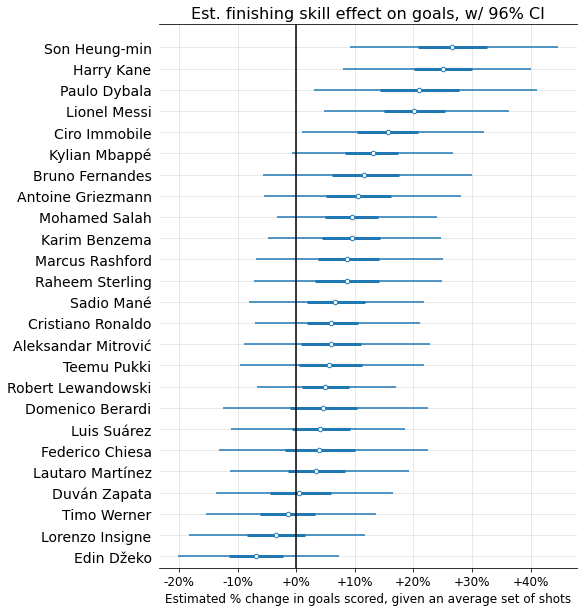

Below are estimated finishing skills (mapped to “% change in goals scored on an average set of shots”), along with interquartile range (thicker line) and 96% confidence interval6 (thinner line), for the 25 players with the most shots in the data.

You may have noticed these finishing skills aren’t centered around 0; this could be a form of selection bias, since it seems likely the players who shoot the most tend to be better-than-average finishers.

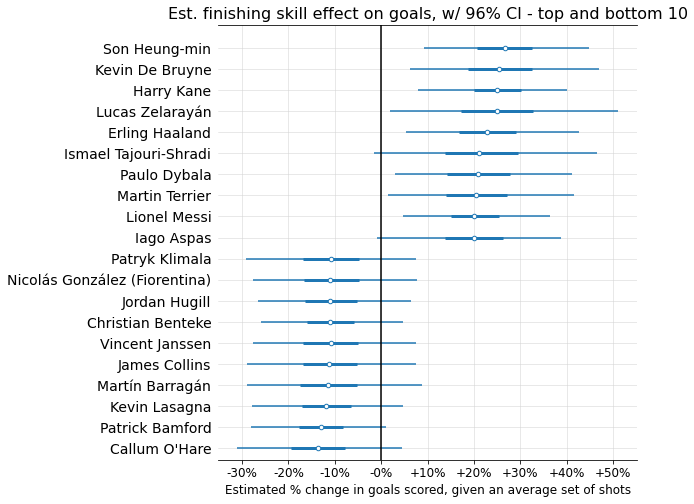

Now, let’s look at the top and bottom 10 finishers, according to the mean skill coefficients estimated by the model:

Not too shocking! A few things worth noticing:

Given the number of shooters (over 7,000) and standard deviation (0.153), there’s a 99% chance that the best finisher in the dataset has a coefficient > 0.46, corresponding to a >38% goal-scoring modifier. But the max value we see here is barely over 25%. What gives?

This is shrinkage in action! While there’s almost certainly some true player coefficient value > 0.46, each individual player has too little sample size for the model to confidently guess that they in particular are this far above average. But you can see that +38% is well within many players’ 96% probability intervals.The top finishers have much more extreme estimated coefficient values than the bottom. While this could indicate that finishing skill is skewed (contradicting my assumption of a bell curve), I think it’s more likely a selection bias issue: the worst finishers tend to take fewer shots, meaning the model tends to “shrink” them more toward the average due to lack of sample size. So the very below-average finishers probably are present in the dataset, but we’re unable to detect them because they don’t take enough shots.

Let’s compare two specific finishers at either end of the spectrum: Harry Kane and Patrick Bamford. Given the same set of shots, the model expects Harry Kane to score ~44.6% more goals than Patrick Bamford (96% confidence interval: 17.9% to 77.9%). In other words, the model’s best estimate is that on average, 1 xG for Harry Kane is worth ~1.44 xG for Patrick Bamford.

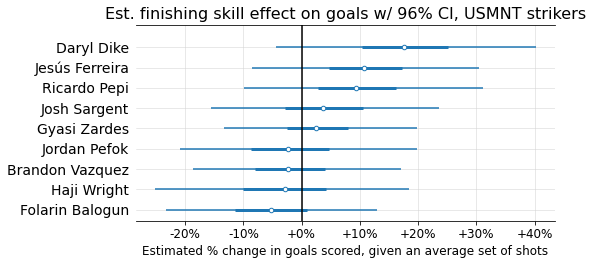

Finally, since I’m American (were there any tells??), I wanted to look at the estimated finishing skills of US strikers who have been in our national team’s depth chart over the past couple years:

A little counter-intuitive for USMNT followers, and I think a salient reminder that ability to create a lot of xG is an extremely important part of one’s goal-scoring ability.

Goalkeeper xG skill

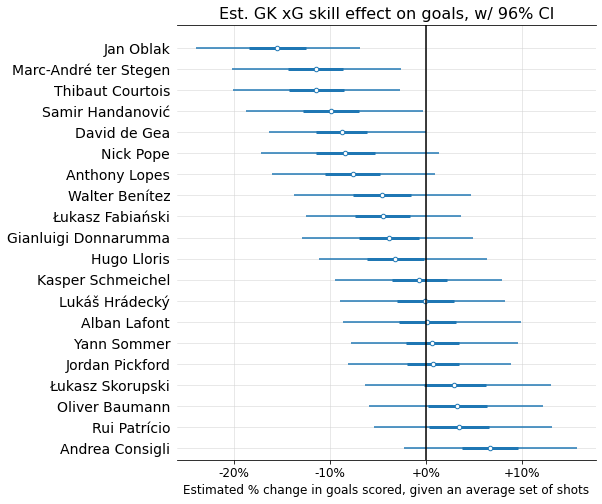

Recall that the model includes not only a skill coefficient for each shooter, but also one for each goalkeeper. As mentioned previously, I don’t think this is a good proxy for overall shot-stopping skill, since it does not reward or punish GKs for good or bad positioning. As such, I think of it as more of a measure of a GK’s ability to make reflex and acrobatic saves, once their position has already been set. (Also, it knows nothing about the actual shot, so this estimate of GK skill will be much less precise than one that relies on, for example, PSxG or xGOT)

To make it clear this measure has limitations, I’ll refer to it by the clunky term “GK xG skill”: a measure of how much each individual GK is able to suppress a shot’s xG.

Below I show the model’s “GK xG skill” estimates for the 20 highest-volume GKs, again mapped to % impact on predicted goals scored for an average set of shots:

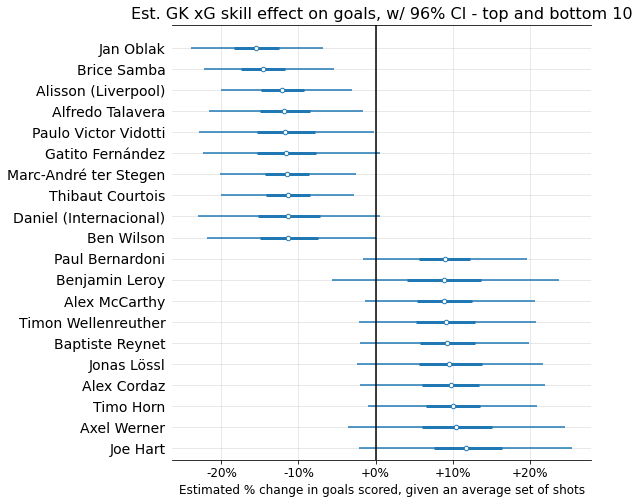

The top and bottom 10 GKs according to the model’s mean skill estimates:

And a few GKs in the US national team’s depth chart:

Shrinkage in action

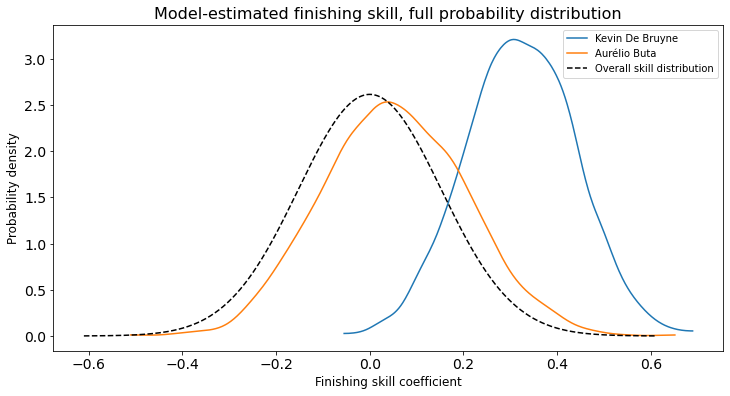

One final thing I’d like to draw attention to is shrinkage, i.e. how the model balances signal against noise. To do this I examine two players: Kevin De Bruyne and Aurélio Buta of Eintracht Frankfurt.

Buta has amazing finishing stats: 3 goals on just 0.64 xG, for a whopping 4.69 G/xG ratio. De Bruyne, on the other hand, has a still world-class but much lower 1.61 G/xG ratio. However, we have only 10 shots of data for Buta, vs. 474 for De Bruyne. Here’s how the model uses the available information to estimate the probability distribution of each player’s true finishing skill:

Since sample size is so low for Buta, the model prudently infers that in all likelihood, most of his remarkable performance is the result of good luck rather than exceptional skill. Ultimately, it predicts that he’s more likely than not an above average finisher, but with a very wide range of possibilities; it basically just shifts the overall skill distribution a little bit to the right, with the amount of uncertainty almost unchanged since 10 is such a low sample size. On the other hand, since De Bruyne has consistently performed so well over hundreds of shots, the model guesses he is likely far above average, with a tighter probability spread as well.

Discussion

So…does finishing skill matter?

I guess that depends on whether you think the estimated level of variance — roughly an 11% standard deviation in goal-scoring rate — is meaningful. (For me, that’s a “yes”)

That said, I’d like to address a real issue here: detectability.

Outcomes data can only take you so far

The framework I use in this article struggles to confidently distinguish player A from player B, even with 5+ years of data! That certainly limits its usefulness for evaluating a single player’s goal-scoring ability, especially for decision-makers who might need to make a judgment on a player with only 1-2 seasons of high-quality data (or less).

However, I don’t think this is a reason to dismiss finishing skill, for at least two reasons.

First, the methodology used here — using only a player’s own binary outcomes (i.e. goals) to determine their skill — is basically the noisiest method possible: binary outcomes require large sample size, and every individual player has a small sample of shots. I really like the way Mike Goodman puts it in “Thinking About Finishing Skill”:

Given how complicated a sport football is, and how rare goal scoring events are in general, we’d never know decisively just by looking at outputs if players managed to increase their conversion percentages, or even teams for that matter. That doesn’t mean that those margins aren’t important, and it certainly doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. It simply means that to find them we may need to start systematically looking at inputs instead. And it’s those inputs which make up finishing skill.

I couldn’t agree more. The model I built for this analysis was optimized for quantifying variance, not for precisely detecting each player’s skill. There are better ways to do that, by adding more inputs (for example player attributes) to the model, thereby enabling it to aggregate over many players’ shots — i.e. a much larger sample — to detect patterns of xG over- or under-performance.

Second, we don’t need to restrict ourselves to tabular data; in fact as humans, we’ve evolved the ability to parse infinitely richer data (like what we see) for patterns. Yes, we suffer from biases and are known to hallucinate patterns; and yes, discourse that tries to extrapolate a player’s finishing ability from a single ugly shot is wasted breath. But I strongly suspect that experienced observers like scouts can do a better job of guessing where a player sits on the finishing skill spectrum than a simple statistical or ML model, given the wealth of information they’re drawing on — especially when these people work in tandem with such models to calibrate their evaluations.

Finishing vs. xG

The final topic I’ll touch on, just briefly, is the comparison between finishing and chance creation (as measured by something like xG/90).

When comparing the relative importance of these two skills in determining overall goal-scoring ability, I think it’s important to keep a few things in mind:

Comparing respective variances is a good place to start. Here, we’ve estimated that the standard deviation in player finishing skill is about an 11% difference in scoring rate. Since scoring rate is basically a multiplier on xG, an equivalent level of xG/90 standard deviation would be something like 11% of its mean

xG depends a lot on a player’s role on the field. Probably it makes the most sense to measure variance within each position, and to focus mostly on attacking positions

xG has much more to do with one’s teammates and opponents than finishing; thus a larger part of xG variance will be due to factors (such as team quality) outside of a player’s own ability. A fully fair comparison of xG and finishing should really try to quantify and account for this

That’s all

To recap:

When talking about how much a skill “matters”, I think we’re really talking about how much it varies across players

So, I built a model to quantify the variance in finishing skill among men’s pro soccer players, avoiding some common “low sample size” pitfalls in variance estimation

Ideally, to really decide how important finishing skill is, we would compare this estimated variance to that of other goal-scoring skills like chance creation (xG); although detectability is an important consideration too

No matter how much clarity we gain on all these things, a question like “Does it matter?” might never allow for a clear answer

I hope you’ve gotten something out of this post. If you have any thoughts, questions, criticisms, etc., please leave a comment so that others can benefit from your ideas too.

If you’d like to see more analyses like this, I’d recommend subscribing — any new posts will go straight to your inbox. And if I never post again (which is a possibility), then you’ll be no worse off :)

The xG model used here controls for many pre-shot factors, including: the location and angle of the shot, clarity of the path to the goal, body part, type of pass, GK position, and more. Importantly, the model does not control for the quality of the actual shot attempt, for example where it was placed (including whether it was blocked) and how hard it was.

The “Bayesian machinery” is any of a number of computational methods that are used to estimate the relative likelihood different parameter values (in our model, the standard deviations of the finishing / GK skill distributions, as well as the logistic regression model coefficients for every individual shooter and goalkeeper). These computational methods eventually spit out probability distributions for all the parameters, from which you can report things like highest density intervals (basically confidence intervals). For this analysis, I use the default MCMC sampling techniques in the Python library PyMC.

The xG model I’m using controls for goalkeeper positioning, meaning that whatever goalkeeper skill the model is measuring will not account for how good or bad a GK’s positioning is. What the model is telling us is probably closer to a GK’s ability to make difficult reflex and acrobatic saves.

While this limits the model’s ability to evaluate overall shot-stopping skill, it’s actually great for evaluating shooter finishing skill, since it enables the model to credit a shooter for placing their shots far from where the GK actually is.

More subtly, this should also improve the validity of comparing finishing skill estimates across leagues: for example, if there’s a league with excellent goalkeeping, the model won’t erroneously learn that the shooters in that league are bad finishers.

Exact leagues and seasons covered are:

Big 5 leagues from 2017-2018 to 2022-2023

Primeira Liga, Eredivisie, and the Championship from 2018-2019 to 2022-2023

MLS from 2018 to 2023, Liga MX from 2018-2019 to 2022-2023, and the Brasileirão from 2019 to 2023

Champions League and Europa League from 2017-2018 to 2022-2023, and the Europa Conference League from 2021-2022 to 2022-2023

2018 and 2022 World Cups, and the 2021 Euros

The data was pulled in mid-July 2023, so for summer leagues (like MLS) the 2023 season is incomplete.

As is common in Bayesian inference, I cheekily use an uncommon confidence level (96%) to remind the reader that 95%, almost universally used in hypothesis testing, is just as arbitrary a choice as any other number and should not be treated as the arbiter of whether or not a measured effect is “real”.

Put differently: you should not think about hypotheses in “true/false” binaries, where they’re true if the p-value is below some arbitrary value (like 0.05) and false otherwise. Rather, you should think about hypotheses on a continuous spectrum of plausibility. 96%, 89%, 50%, etc. intervals all carry exactly as much information as a 95% interval, and the hope is that by using a non-standard value, you the reader are shaken into a greater awareness of what these probability intervals actually mean.

The textbook that really changed my perspective on this is Statistical Rethinking by Richard McElreath. In particular, Chapter 1, “The Golem of Prague”, fundamentally changed the way I think about hypothesis testing specifically, and philosophy of science more generally.